No really, this is my LinkedIn password:

y>8Q^<6mqKEA4hac

Well it was my LinkedIn password until earlier today when it became apparent that LinkedIn had suffered what could only be described as a massive security breach. The disclosure of 6 million passwords used in one of the world’s premier social networking sites is nothing short of astonishing.

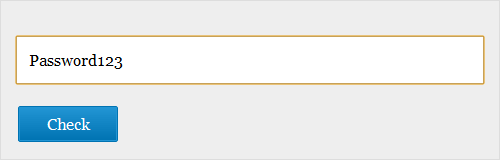

But what’s also astonishing is that this exercise once again demonstrates that we, as users, are continuing to choose outrageously stupid passwords. How do I know this? Take a look at leakedin.org and try something obvious:

And here it is:

![]()

Now try your old LinkedIn password which, of course, you’ve already changed. Don’t worry, the site hashes it in the browser then sends the hash to the server to match against the LinkedIn breach. Still don’t trust it? Is that because you’re concerned about the other places you’ve used that password? And therein lies the problem.

Password strength basics

For the purpose of this post, it doesn’t particularly matter how the LinkedIn passwords were obtained, all that matters is that they were. Several security researchers have verified the presence of their passwords in the dump and these are now accessible to anyone who wants to go and grab a copy.

This is what tends to happen when sites get breached: suddenly all the accounts are out there for one and all to see and there’s a long queue of people lined up waiting to see what your password choice is. Chances are you’ve used it somewhere else before and guess what that means? Yep, suddenly you start tweeting about Acai berries.

LinkedIn weren’t entirely negligent with the way they stored password, just mostly negligent! What they did is use a cryptography practice which makes it exceptionally easy to expose weak passwords. What’s a weak password? It’s a password which doesn’t adhere to these three tenets:

- Uniqueness: You haven’t used it anywhere else before. Ever.

- Randomness: It doesn’t adhere to a pattern and uses a combination of upper and lowercase letters, numbers and symbols.

- Length: It has as many characters as possible, certainly at least a dozen.

When your password doesn’t follow these three basic practices it becomes vulnerable to “brute force” or in other words, a hacker who has hold of a password database has a much greater chance of exposing even cryptographically stored passwords.

How? Well in terms of uniqueness, the password could well be found in a password dictionary. For example, you would not want to use the password ”correct horse battery staple” as this is now well known. Likewise many other password combination – regardless of randomness and length – appear in these dictionaries and can be easily matched to even a cryptographically stored version such as in the case of LinkedIn. Character substitutions such as “p@ssw0rd” (or similar variants) are also popular dictionary entries.

Randomness and length all come down to probability; the more likely your password is to fall within a very limited range, the more likely it is to be cracked. What range are we talking about? Based on previous analysis, six to eight characters and entirely uppercase or lowercase covers a vast spectrum of passwords. The speed at which these passwords can be “cracked” is exceptionally fast due to their predictability of falling within such a constrained range.

How to remember store passwords

If you can remember your (new) LinkedIn password, you’ve chosen poorly. Either that or you’re doing your other passwords wrong because you simply cannot remember unique, random, long passwords. You might get two out of three – perhaps randomness and length – but you can’t do that for each of your accounts so there goes your uniqueness.

Screwy memory patterns don’t work – the only secure password is the one you can’t remember. I’ve heard every memory pattern under the sun and they are consistently complex, verbose or impractical.

Which brings us neatly to password managers. Get one. It’s easy to get up and running with my personal favourite, 1Password and I hear good things about LastPass and KeePass too.

So why am I sharing my (old) LinkedIn password?

Because I can. Because the password was randomly generated and used absolutely nowhere else. Once changed, that old password holds zero value. Anywhere. If you can’t say the same thing about your (old) LinkedIn password then it means you now have a problem you need to go away and fix.

Having a password manager and using it correctly is a liberating experience. It makes the difference between a breach like LinkedIn being nothing more than a minor inconvenience versus a potentially serious episode with the real possibility of identity theft and other nasty consequences.

At the time of writing, the LinkedIn breach consists of “only” 6.5 million passwords (they have 150 million registered users), and as yet, there have been no usernames or email addresses publicly released. Chances are though that these will soon follow and the folks that haven’t been applying that unique / random / long trio will get a crash course in why password selection is important.