I have two enduring loves beyond the commonly accepted ones of health and family: technology and fast cars. It’s hard to be passionate about these two and not lust after a GT-R so after some years of lusting, I bought one. Being a technology blog, it wouldn’t be right not to share some of the goodness found within this machine so allow me to give you a taste of what happens when you cram enough cycles of computing power into four wheels and forgive me if the excitement boils over just a little bit :)

In case you’re not a car person, this is a GT-R:

Actually that’s the one decent shot I have of mine (the rest are stock photos) and it’s a Nissan, Jim, but not as we know it. The Japanese have been making GT-Rs on and off for 44 years now but they really gained notoriety in the 90s as the top spec variants of their Skyline model. Down here where we only got a few of the machines on the local market, the Aussie press named it “Godzilla” for its monstrous performance ability and motorsport domination. The name kinda stuck around the world. It was so dominant in our local motorsport that it lead to the now infamous pack of arseholes speech by our racing luminary Jim Richards after continued domination of a category that was usually the domain of rather mechanically basic front-engine, rear wheel drive V8s.

There was a 7 year GT-R hiatus from 2002 but come 2009 the car you see above arrived although this time it was built as a GT-R from the ground up and was no longer a hot version of the Skyline platform. From the outset, Nissan set a massively high performance bar clearly targeting Porsche’s 911 Turbo and spending a great whack of time on Germany’s Nürburgring (a long time benchmark for performance cars) and generally did a lot of chest-beating about Anyone, Anytime, Anywhere.

That’s enough of the history lesson, let’s get into the good bits! And yes, there is some video I’ve put together down the very end.

Background

Just a quick bit of context; the GT-R has replaced my much-loved, much “exercised” Subaru WRX STi:

Clearly it didn’t lead a gentle life! The STi was regularly used for club motorsport events, most often in “rally skills” events which were predominantly skidpans and dirt motorkhanas so it got a lot of this. It was a great car, very well setup with just the right modifications for both road and track and took me to a club championship back in ‘07. It got some track time but I mostly got that out of my system with the previous WRX which saw a heap of competitive motorsport between 2000 and 2005 which meant a lot of this (class record that day too, thank you very much!)

So fast cars and active involvement in motorsport have been a passion for many years now and brought many fantastic experiences. In more recent years I’ve kept track time mostly to instructing duties (c’mon, who doesn’t want to drive other peoples’ fast cars on a racetrack?!) but the interest – the passion – has never wavered. These experiences have influenced my choice of car in the GT-R and naturally these are the comparisons I’ll draw so hopefully that sets some context and saves the inevitable comments around “are you sure you can handle this new beast?!” :) In the immortal words of Ricky Bobby, I wanna go fast! (in a controlled environment with the appropriate training and experience etc. etc.)

Performance

Let me start at the pointy end – the GT-R is ridiculously fast! I’ve been fortunate enough to drive a whole lot of fast cars on road and track but this is just another echelon of anything I’ve been near before. One of the best party tricks of the car is the ability to get from zero to 100 kph in under 3 seconds. Yes, that’s 3 as in t-h-r-e-e. A video speaks a thousand words here:

That's pretty much it – a combination of awe and laugh-out-loud disbelief at what the thing can do. I’ve taken a few people for drives now and the reaction is always simply sheer disbelief mixed with terror – you want to keep going back and doing it again and again. Basically the reaction is always just like this (really wish I’d filmed some of them now).

The traction is what really makes it and that’s partly due to all wheel drive but as James says in the video above, it’s also due to the massive amount of computing power that’s able to assess the amount of slip that’s happening and control the electronic throttle – as well as front and rear torque distribution – that enables those astronomical acceleration figures.

In the isolated video above, it looks fast, but it’s not until you get some perspective against cars like the Ferrari 458 or V10 Audi that you get a sense of where that massive acceleration comes from:

It’s grip – massive, almost unparalleled traction (at least this side of a Bugatti Veyron) that gives the GT-R the jump. Once other cars with similar power but less weight hook up the game starts to change, but by then there’s several car lengths to be made up. Being all wheel drive is a significant part of it, but then the R8 GT is all wheel drive and has another 30 bhp (although a bit less torque) but 200 kg less weight and a fair whack more tyre size on the rear. There’s just a whole heap of smarts going on in the GT-R to carefully manage the balance of power delivery versus traction and at lower speeds where the former can easily overcome the latter, that’s a pretty critical attribute.

Going fast in a straight line is great, don’t get me wrong, but there are plenty of cars that can do that. Laying down a fast track time is a far more involving pursuit as now you’re looking at chassis dynamics, breaking, aero, durability plus of course power. Getting back to that Nürburgring lap, the 2010 model (which they call the 2011 model in America – you know, the one that was released in 2010!) got around in 7 minutes and 24 seconds. Some perspective helps here – go back to the lap records and that’s faster than a Pagani Zonda F Clubsport:

And even faster than a Ferrari Enzo:

Frankly that all gets a bit academic – newer GT-Rs are faster (allegedly 7:18), other cars are in the ballpark (Corvette ZR1 at 7:20, Porsche 911 GT2 RS at 7:24 etc.) and that’s all great for bragging rights but not a whole lot else. Different tracks, different drivers different temperatures (turbos love cold, dense air) and everything changes.

Thing is though, you can fit the kids in the back of the GT-R and drive to the shops in it. Here’s what that Nürburgring lap looks like and frankly, some of it’s a little bit frightening:

Since that model there have been three annual refreshes that have brought more power, more torque plus gearbox and handling improvements. The thing that makes the GT-R a bit of an enigma in terms of speed is that it’s doing it with significantly less power-to-weight than cars like the Zonda and the Enzo – and that’s where the tech comes in. Let’s take a look under the covers and bit into the bits and bytes of what makes this a little bit special.

Dual clutch gearbox

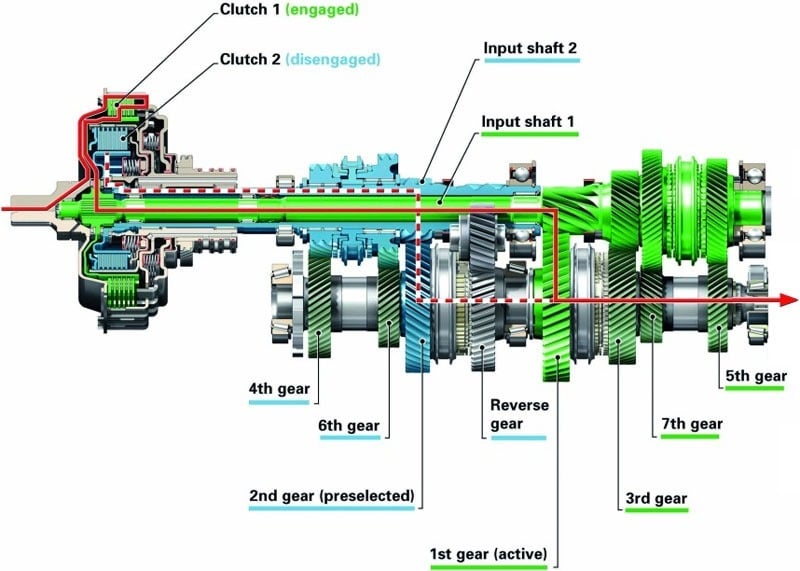

Here’s the thing with gearboxes – and some people aren’t going to like this – the manual box is dead. No really, we got over a century out of them so they had a good run, but they’ve now been comprehensively superseded by modern alternatives. The most popular modern day successor involves automating the control of two separate clutches connected to their own gear sets (one with the even ones, one with the odds) and controlling the whole thing via clever software. We normally refer to this as a dual clutch ‘box and it looks like this:

This is a seven speed Audi box but it illustrates the principle really well. In this example you can see the two clutches in the upper left with the first one which drives the odd gears activated and the second disengaged. You can see the 2nd gear already “preselected” or in other words, positioned such that once the second clutch is engaged everything is already in the right place. What it means is that changing up only involves disengaging the first clutch then engaging the second. Choosing which gear to preselect is simple conditional logic – accelerating? Get the next gear up ready. Braking? Get the next gear down.

The GT-R can complete the shuffle between clutches in about 100ms. Compare that to the process in the manual box – come off the throttle, depress the clutch via foot, select the next gear via hand, release the clutch then get back on the throttle. You’re looking at 500ms and up in most cases which is why the dual clutch boxes consistently out-accelerate the manual brethren to 100kph by a couple of hundred milliseconds. Get yourself into something like a Pagani Zonda Revolucion and the shift times are down to only 20ms which is mind boggling for what ultimately remains a mechanical process.

For daily driving, a dual clutch box means that software can start to do very clever things like pick the optimal gear for fuel efficiency. In fact this is another key reason why manufacturers – even of high performance vehicles – are going dual clutch as it means improved emissions results which they’re increasingly under pressure to achieve. As a driver, it means you can whack it in “auto” and drive it around just like a traditional automatic box but without the lethargy the vast majority of them suffer from. In fact for smart enough software, the car can even start to pull tricks such as satellite aided transmission as seen in the Rolls Royce Wraith where it will select the right gear based on the angle of the upcoming corner. Cool. I think.

This is all great for the daily commute in city traffic, but then you also get these:

Paddle shifters mated with a dual clutch box on a performance car give you new ways of driving. Firstly, you’re usually not taking your hands off the wheel to shift (unless you’ve wound on a lot of lock, usually at lower speed) so there’s no more either short shifting or holding higher RPM than you otherwise would or compromising on control by releasing the wheel. Then when you do shift up, the speed of the change means the flow of torque is almost unrelenting so it doesn’t unsettle the vehicle in the way it does in a manual. Many a driver has made an unexpected acquaintance with the concept of lift-off oversteer trying to shift up mid-corner!

The other thing about computers controlling the gearbox is that you get to do tricks like this:

These are toggles for the transmission, suspension and vehicle dynamic control (VDC). The idea of adjusting these is that you get some control over aggression versus comfort. What does this look like? Well for example, when you’re driving around in auto mode (i.e. the computer decides when to shift), comfort mode won’t change gears as eagerly in response to changes in throttle position. Whack it into race mode and it’ll change far more vigorously and hold the gear for longer. Drive it in “manual” race mode and it’ll let you rev into redline. The computers aren’t always going to get it right, but a combination of different settings and learning how it responds to driver inputs gets you a pretty damn good balance.

I’ve had a great time with manual performance cars over the years; I couldn’t imagine a skidpan session without being able to pop the clutch for a sudden whack of traction-breaking torque and there were few moments as satisfying as a cleanly executed heel and toe in something as simple as a Mazda MX5 on the track. Then again, cars like the new Porsche GT3 (which now only comes in a dual clutch) can engage the clutch by pulling both paddles (remember folks, it’s only software) and as for the satisfaction of driving a manual quickly, that was more about the ability to overcome a challenge than it was about going fast!

Front-engined, rear-mounted transaxle gearbox

Here’s how your typical drive train gets put together: Engine and gearbox go into the front, drive goes out to the wheels and if that means the rear ones (either rear wheel drive or all-wheel drive) then you get a single drive shaft sending torque to a rear diff. Of course there are variances (namely mid-engined vehicles like a Ferrari 458 or rear-engined like a Porsche 911), but this architecture accounts for the vast majority of vehicles out there.

The problem is that this means a hell of lot of weight goes into the front of the car and the problem with that is that it doesn’t do great things for balance. There’s a lot of inertia sitting over the front wheels which means turn-in suffers (the ability quickly tip the car into a corner) as that great big whack of mass up front wants to keep travelling in straight line rather than changing direction. A gearbox is also a big piece of kit so putting it up front causes other compromises such as pushing the engine even further forward therefore exaggerating the forward leaning weight problem, pushing it up higher which impacts the centre of gravity and increases body roll or protruding into cabin space. But putting the engine and gearbox up front is extremely cost effective plus it means you can actually do something with the space at the back of the vehicle, such as put stuff in it!

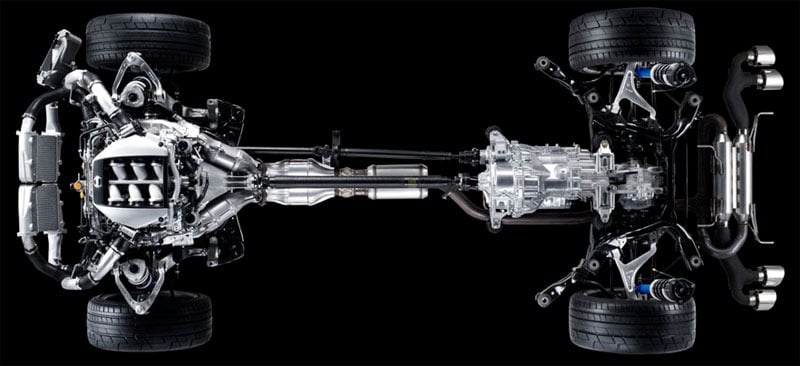

Here’s what the GT-R does:

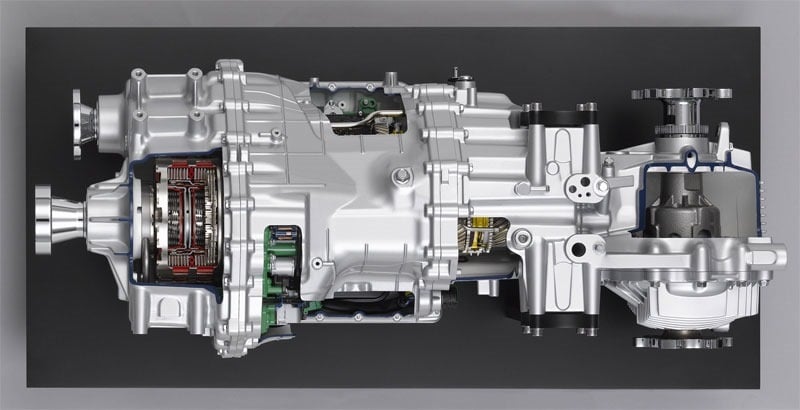

You can see the gearbox sitting down under the rear seats which means a whole lot of weight moves backwards. Not an even amount, mind you, there’s still 53% over the front axle but that’s an exceptionally good balance for a front-engined vehicle. The transaxle part comes in when the rear diff is baked into the gearbox rather than being a separate unit which means it looks like this:

The right side of the picture shows the diff mounted to the rear of the gearbox and it’s from here that drive is sent to the rear wheels. Back on the left hand side you can see a cutaway exposing the clutches just behind where drive enters the box.

This approach isn’t unique to the GT-R, the same front-engined rear-mounted transaxle configuration can be found in cars like the Ferrari F12 Berlinetta and Mercedes SLS AMG. However, here’s the big difference with the GT-R:

Unlike the European comparables, the GT-R is all wheel drive so it has to get torque from the gearbox back up to the front wheels and therefore has a second drive shaft which you can see just above the centreline of the vehicle (you can also see the mounts for this in the top left of the prior gearbox picture). This makes it unique for a transaxle configuration and whilst a bit verbose in terms of the hardware required, it means it gets that beautiful weight distribution between front and rear.

Incidentally, the primary drive shaft from running from the engine to the gearbox is a carbon composite job. Very light, very little flex and extremely strong.

Engine

It’s a 3.8 Litre V6 but that alone isn’t what makes it special, there’s a number of different tricks that turn the otherwise rather mainstream capacity into something altogether more ballistic. The most obvious addition is a couple of turbos, each one feeding into a cylinder bank either side of the longitudinally mounted engine. It all looks a bit like this:

You can see it mounted as far back as possible in the engine bay which is another part of the great front-to-rear weight distribution I touched on earlier.

The bores don’t have cylinder liners, instead they’re plasma coated or more specifically, plasma transfer wire arc thermal sprayed. This takes the mass of the traditionally cast iron liners out of the engine.

Then there’s the turbos:

Ordinarily, each of the units you see above would be two separate parts; the turbo (consisting of both the exhaust and intake turbines) and the headers which take emissions from the engine then feed it down usually some distance (depending on the engine packaging) through exhaust plumbing. The GT-R packs the exhaust turbine into the header (you can see it’s one cast unit) so the packaging is smaller and the lag between engine and turbine is reduced.

Poking around the car shows up all sorts of tricky packaging, cooling and general tricks to extract the levels of performance it achieves, not just for short bursts but for prolonged high performance driving.

Instrumentation

Here’s the real tech porn bit that’ll resonate with the inner-techie – the multi-function display:

This is like Task Manager for cars and it can spit out a wealth of information in different formats. Instrumentation in vehicles – even high performance vehicles – is usually limited to things like speed, RPM and a very vague engine temp gauge. In the GT-R, you get stuff like this:

Longitudinal G forces (i.e. the rate of acceleration) combined with boost pressure (effectively how hard the turbos are working to force air into the engine) and the amount of acceleration potential actually being used. But that’s just the start, you also get stuff like this:

The distribution of torque from front to rear is especially interesting as it can dramatically change the behaviour of the car. The STi had the ability to shuffle torque backwards and forwards as well but there was always a significant portion going through the front wheels which made it hard to exploit some of the more desirable attributes of a rear wheel drive platform such as power-on oversteer.

All in all, you get 18 different system metrics that can be represented on the LCD:

- Engine Coolant Temperature

- Engine Oil Temperature

- Engine Oil Pressure

- Transmission Oil Temperature

- Transmission Oil Pressure

- Boost

- Speed

- Fuel/Range

- Fuel Flow

- Recent Fuel Economy

- Torque split

- Accel pedal

- Brake pedal

- Steering angle

- Cornering g-force

- Accel/Braking g-force

- Total g-force

- Clock (yay!)

The manual for the MFD goes on about the various functions and how they can be represented on screen and frankly many of them are not a lot of use. Things like g-forces are kind of neat for geek value, but even on the track you’d go for dedicated instrumentation designed for maximising lap times. Fluid temps, however, really are useful and once you have an accurate oil temp gauge (as I did courtesy of an aftermarket one in the STi), you realise just how long it takes the car (any car, for that matter), to get to a temp where oils are actually at an optimal temp to do their job properly. Many a car has been driven hard too early and suffered rather unpleasant consequences as a result.

Aero

There are two big problems cars face the faster the go: drag and downforce. Too much of the first seriously dents acceleration (and fuel economy), not enough of the latter makes it harder to go around corners at pace. But the two objectives can also be counter-productive as creating downforce also crates drag. This is one of the reasons why we’re seeing more and more active aerodynamics so the car can be sleek when it needs to but then disrupt the airflow enough to apply downforce to different parts of the vehicle as required (check out the flaps on a Pagani Huayra if you’re not sure what this looks like). But I digress…

The GT-R focuses primary on drag and as a result has very low drag coefficient of 0.26, about lineball with a Toyota Prius. Against the competition, that’s amazingly efficient: Porsche Turbo is 0.31 (less is better when it comes to drag), a Ferrari California is 0.32 and even a recent model Corvette is 0.29. You’ll get slightly lower than that on some economy-focussed cars (take a few hundredths off) but you need to remember that performance cars are also trying to generate downforce so the previous performance car comparables are the real interesting bits.

So how does it do it? Aero always comes downs to lots of little tweaks, for example the door handles:

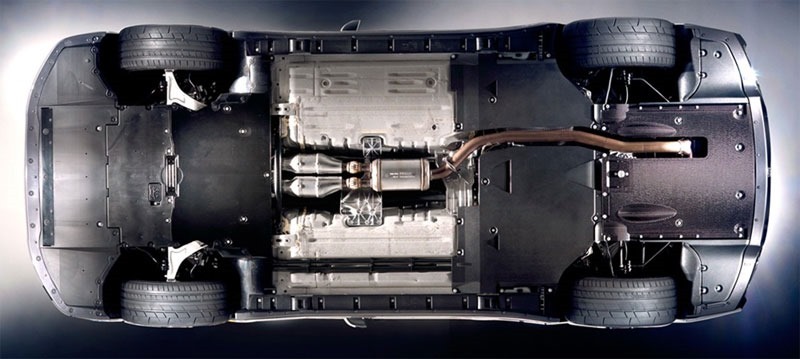

Of more significance is the underbody (in fact a huge amount of drag originates under the chassis):

You can see the smooth profile courtesy of scuff plates, a diffuser and other facades that attempt to smooth the airflow by keeping all the pointy bits out of the way. But there’s a whole lot of subtleties that aren’t immediately obvious; I put mine up on the hoist at my mechanic’s last week and found a whole bunch of goodies. For example, the three cooling ducts you can see in the black panels just in front of the rear wheels. That middle one feeds air directly onto the heat sink on the gearbox then passes it out through the duct behind it. There’s also a phenomenal amount of bracing, for example you can just see the vertical bar in front of the two catalytic converters behind the panels under the front of the car. There’s another very significant brace just behind the cats which passes over the exhaust just before the two pipes go into one. Not exactly aero any more but quite interesting whilst we’re looking at the underside.

Then of course there’s the entire body profile with that classic coupe shape which is always going to play nice with airflow:

One thing that’s very unique about the GT-R though is the hard edges on many of the surfaces. You can see it on the trailing edge of the vents just behind the front wheels in the picture above but it’s really evident when you look at the way the sides of the body join the rear of the car:

They’re damned near right angles and the lighting in that pic really illustrates just how sharp the lines are. Aesthetically, it doesn’t have the beauty of a curvaceous Porsche 911 but there’s something very functional, very Japanese about the whole design.

One of the things that really bugs me in automotive design is over-design; features that have no functional value and just appear tacked on for some sort of odd aesthetic value. Think Apple’s skeuomorphic approach (and we all know how that’s ended up). For example, I thoroughly dislike how Subaru has added faux vents to the front and rear bumpers:

You know what these are? Speed holes:

Living with the GT-R for a little while you start to notice all the aero nuances that don’t really come through in the pictures earlier on, things like the protrusion beneath the wing mirrors (a particularly aerodynamically inefficient piece of equipment):

Or the subtleties in the rear wing design like the slightly raised ends, streamlined protrusions just above the mounting points or just how far back beyond the boot lid it actually extends:

Then there’s the vents behind the front wheel arches – real vents – that draw heat from the engine bay through the negative pressure area created behind the contour of the arch:

All of this (and much, much more) adds up to contribute to that low drag coefficient. It’s little pieces like the drag, the transmission and the grip that add up to that massive performance that’s so far beyond what it should be capable of based on power and weight alone. The big question though is:

But what’s it like to drive?

Violent. Well actually, it’s docile then it’s violent, I mean you can drive it around town in auto with everything in comfort mode and it’s not much different to many mainstream cars. Probably the main compromise is the ride although it’s still comfier than the STi and the ground clearance is only fractionally less. But then you flick the transmission and traction into R, whack the shifter into manual mode and it all goes a bit Millennium-Falcon-in-hyperdrive.

First gear can’t get all the power down so the traction control has a job managing that before you whack into the rev limiter. Second hits hard as the RPM is already up there so it pulls very strongly into third and that’s about as much as I can, uh, publicly say until it sees a racetrack :)

What I can say though is that in second the back will still let go if tipped into a corner hard enough and that’s on a bone dry road. The traction control in race mode though gives it a big whack of slip and combined with some opposite lock it pulls it back dead straight (if you’re quick) and just powers on to redline. Probably the biggest surprise actually is just how rear-orientated the power delivery is, in many ways it drives more like the powerful rear wheel drive cars I had before the Subarus. The latter would tend towards understeer and the only way you’re getting out of that is to ease off the throttle while the former would oversteer at the drop of a hat and need to be balanced on the throttle and steering, assuming you weren’t already facing in the wrong direction.

Again, it’s the computers that nail it in the GT-R. They give you the slip to get tail happy but reign it in at just the right time to not just save you from yourself but to go faster than if they weren’t there. Times gone by (and in many current generation cars), the computers just get in the way behaving in an obtrusive fashion that kills both fun and pace. Top Gear mag summarised the modern day electronic nanny as follows:

These days, you don’t drive around the traction-control systems. You drive straight into them, and go faster

That’s what it feels like in the GT-R – not intrusive at the limit of adhesion (at least not in race mode), rather complimentary in the best way possible in terms of outright speed. Like the WRX though, the grip thresholds are that much higher than your average performance vehicle that when it does let go it can be at a serious rate of knots which means it might not always end well.

The other thing about the GT-R is the reaction it brings out of others. The day my wife and I got the car we had schoolkids and senior citizens alike come up and talk about it, the latter couple describing how this was their son’s dream car and would be the first purchase after a lotto win before a house (pro tip: invest first then buy toys!) The enthusiasm extends to the road with other cars regularly jostling for the right spot so the driver can unashamedly ogle the black beast. Even kids on bikes the other day were stopping mid-crossing and gawking then giving thumbs up and leaving with big smiles. Whilst I’m sure not all run ins will be positive, most of them pretty much go like this and that can really make your day :)

Speaking of kids, yes, they fit. Frankly that’s one of the most significant things about the car, that it can do everything above and still carry family. It’s not the family car and nor will it ever be, but it can comfortably get away with it when it needs to. On the practicality front, the fuel economy was a bit of a shock – it’s better than the STi by a fair margin and even fractionally less than our R36 VW (the real family car). A week of Sydney traffic commute would normally see the Subaru around 15.5L/100km and the dub dub about 14.5, the GT-R has been running at low 14s which is a rather nice surprise. I suspect it’s a combination of the fact that it gets into high gears quickly and has enough torque to maintain them without constantly shuffling them. It’s a lot more stable than the DSG in the VW in that regard.

Enough of that, let’s get to the drive video and if you’re just after the windy road bits, flick through to 15:00 with the best sections of road from about 21:00. It’s only public roads and there’s mostly armco on one side and rocks or trees on the other with no run-off (plus the desire to preserve my license!) so until I get to a track it’s going to be a bit restrained. What doesn’t really come through looking at it again now is just how brutal the acceleration is out of corners, that and the smoother you drive the slower it looks so I’ll try and sort out some better camera angles on track.

Apologies for the slight static and for some rather mundane sections, I recorded the audio on iPhone and didn’t realise the mic was rubbing on my shirt then I realised I don’t know what the hell I’m doing in iMovie and cropping things just got too hard. Sorry!

Next

Where do you go from here? Well firstly, I’ll give it some track time but don’t feel the same itch like I did a decade ago. I’ll probably take it out for some demo runs next driver training day and enjoy it with others. Then there’s always mods – do enough work and they’re significantly outpacing a Bugatti Veyron Supersport. We don’t really have either the roads or motorsport events down here to take advantage of that sort of behaviour but the classic exhaust and tune may feature later on.

But for the most part, it’s now just about enjoying the machine, reflecting on the path that has taken us here and trying to get out of the city more to actually enjoy it. Oh – and sharing the experience with friends. So who’s coming for a ride? :)