Where is your data on the internet? I mean, outside the places you've consciously provided it, where has it now flowed to and is being used and abused in ways you've never expected? The truth is that once the bad guys have your data, it often replicates over and over again via numerous channels and platforms. If you're able to aggregate enough of it en masse, you end up with huge volumes of "threat intelligence data", to use the industry buzzword. And that's precisely what Ben from Synthient has done, and then sent it to Have I Been Pwned (HIBP).

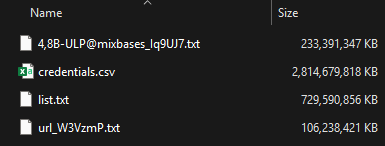

Ben is in his final year of college in the US and is carving out a niche in threat intelligence. He's written up a deeper dive in The Stealer Log Ecosystem: Processing Millions of Credentials a Day, but the headline gives you a sense of the volumes. Have a read of that post and you'll see Ben is pulling data from various sources, including social media, forums, Tor and, of course, Telegram. He's managed to aggregate so much of it that by the time he sent it to us, it was rather sizeable:

That's 3.5 terrabytes of data, with the largest file alone being 2.6TB and, combined, they contain 23 billion rows. It's a vast corpus, and if we were attempting to compete with recent hyperbolic headlines about breach sizes, this would be one of the largest. But I'm not going to play the "mine is bigger than yours" game because it makes no sense once you start analysing the data. Part of what makes the data so large is that we're actually looking at both stealer logs and credential stuffing lists, so let's assess them separately, starting with those stealer logs.

Stealer Logs

Stealer logs are the product of infostealers, that is, malware running on infected machines and capturing credentials entered into websites on input. The output of those stealer logs is primarily three things:

- Website address

- Email address

- Password

Someone logging into Gmail, for example, ends up with their email address and password captured against gmail.com, hence the three parts. Due to the fact that stealer logs are so heavily recycled (they're posted over and over again to the sorts of channels Ben monitors), the first thing we always do is try to get a sense of how much is genuinely new:

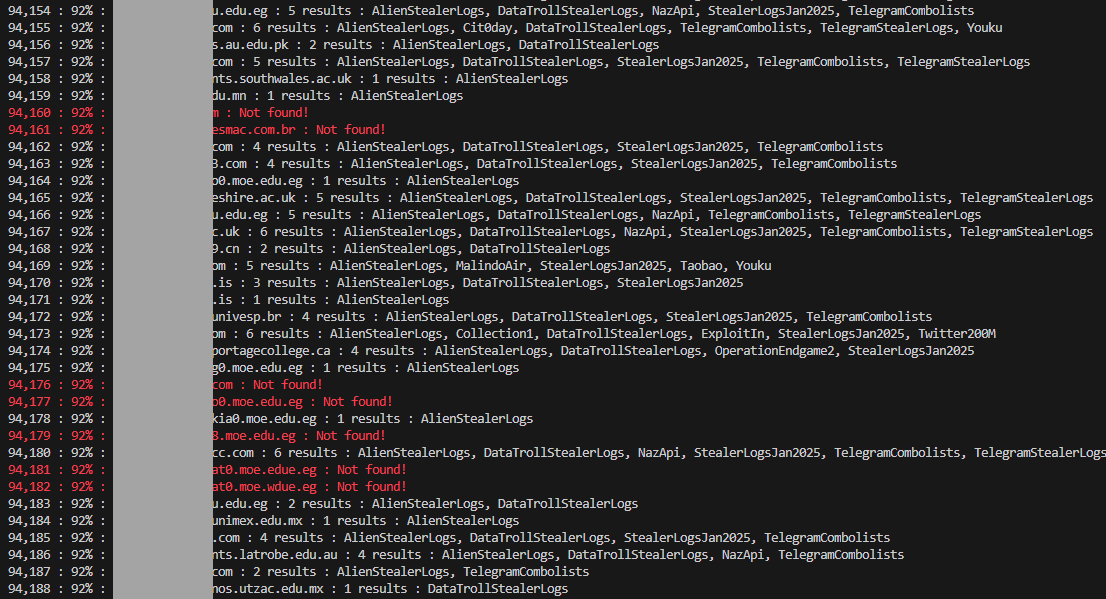

This is the output of a little PowerShell script we use to guage where the email addresses in a new breach corpus have been seen before. Especially when there's a suspicion that data might have been repurposed from elsewhere, it's really useful to run them against the HIBP API and see what comes back. What the output above tells us is that after checking a sample of 94k of them, 92% had been previously seen, mostly in stealer log corpuses we'd loaded in the past. This is an empirical demonstration of what I wrote in the opening paragraph - "it often replicates over and over again" - and as you can see, most of what has been seen before was in the ALIEN TXTBASE stealer logs.

Back to the console output again, and having previously seen 92% of addresses also means we haven't seen 8% of the addresses. That's 8% of a considerable number, too: we found 183M unique email addresses across Ben's stealer log data, so we're talking about 14M+ addresses that have never surfaced in HIBP. (The final number once the entire data set was loaded into HIBP was 91% pre-existing, with 16.4M previously unseen addresses in any data breach, not just stealer logs.) But as with everything we load, the question has to be asked: Is it legit? Can you trust the shady criminals who publish this data not to fill it with junk? The only way to know for sure is to ask the legitimate owners of the data, so I reached out to a bunch of our subscribers and sought their support in verifying.

One of the respondants was already concerned there could be something wrong with his Gmail account and sure enough, he had one stealer log entry for "https://accounts.google.com/signin/challenge/pwd/1" with a, uh, "suboptimal" password:

Yes I can confirm that was an accurate password on my gmail account a few months ago

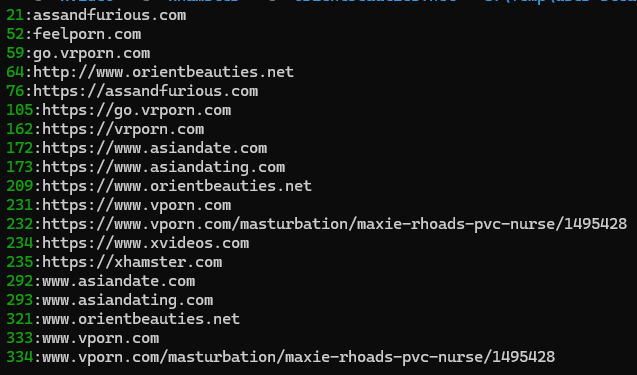

Another respondant who offered support had somewhat of a recognisable pattern in the sites he'd been visiting:

To his credit, he responded and confirmed that the list did indeed contain sites he'd visited, which also included online casinos, crypto websites and VPN services:

They all look like websites I have used and some still do use

As it turns out, he also had two other email addresses in the corpus of data, both with the same collection of passwords used on the first address he replied from. They also both aligned to services based on the same TLD as the other email address which suggested which country he's located in. (Incidentally, the online privacy offered by VPNs kinda falls apart when there's malware on your machine watching every site you visit and recording your credentials.)

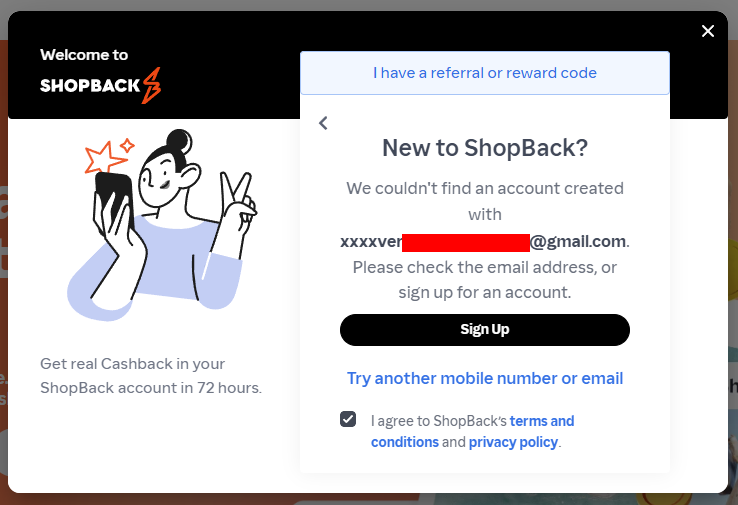

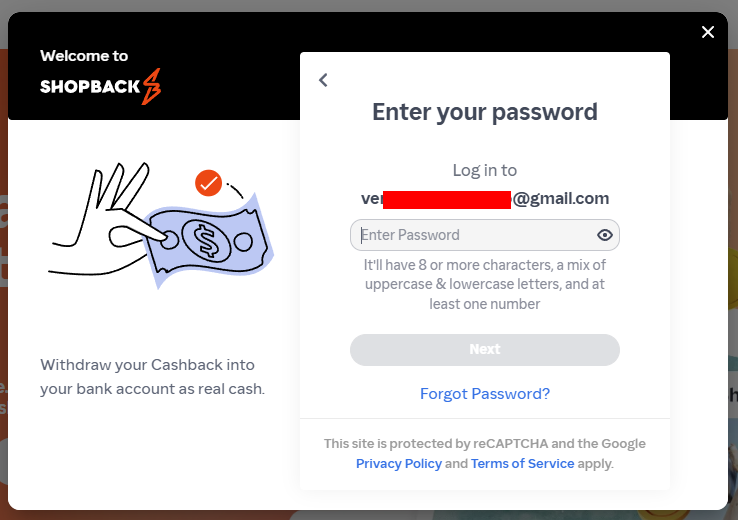

Even without a response from a subscriber, it's still easy to get a sense of the legitimacy of the data in a privacy-preserving fashion (i.e. not logging in with their credentials!) just by testing enumeration vectors. For example, one subscriber had an account at ShopBack in the Philippines which offers what I'll refer to as "account enumeration as a service":

I simply added some character's in front of the email address and ShopBack happily confirmed that address didn't exist. However, remove the invalid characters and there's a very different response:

All of these little "tells" add up; another subscriber had a high prevalence of Greek websites they used, showing exactly the sort of pattern you'd expect to see for someone from that corner of the world. Another had various online survey sites they'd used, and like our "assandfurious" friend from earlier, a clear pattern emerged consistent with the apparent interests of the address's owner. Time and time again, the data checked out, so we loaded it. Those 183M email addresses are now searchable in HIBP, and the passwords are also searchable in Pwned Passwords, which has become rather popular:

Pwned Passwords just served 17.45 billion requests in 30 days 🤯 That's an *average* of 6,733 requests per second, but at our peak, we're hitting 42k per second in a 1-minute block. Crazy numbers! Made possible by @Cloudflare 😎 pic.twitter.com/Io6u1PiqJf

— Troy Hunt (@troyhunt) October 17, 2025

The website addresses are also now searchable, either in the stealer log section of your personal dashboard or by verified domain owners using the API. You'll find this data named "Synthient Stealer Log Threat Data" in HIBP, but stealer logs are only part of the Synthient story - the small part!

Credentials Stuffing

Ben's data also contained credential stuffing lists. Unlike stealer logs, which are the product of malware on the victim's machine, credential stuffing lists are typically aggregated from other places where email address and password pairs are obtained. For example, from data breaches where the passwords are either stored in plain text or protected with easily crackable hashing algorithms. Those lists are then used to access the other accounts of victims where they've reused their passwords.

Quick sidenote: Credential stuffing lists can be enormously damaging because they contain the keys to so many different services. Not only are they the gateway to so many takeovers of social media accounts, email addresses and other valuable personal resources, they're also responsible for many subsequent very serious data breaches. The 2017 Uber breach was attributed to previously breached employee credentials. Five years later, and the same approach provided the initial access to Uber again, after which MFA-bombing sealed the deal. Then there was the 23andMe breach in 2023, which was also traced back to credential stuffing. Similar but different was when Dunkin' Donuts had 20k customer details exposed in a show of how multifaceted this style of attack is: they were subsequently sued for not having sufficient controls to stop hackers from simply logging in with victims' legitimate credentials. It's wild; it's the attack that just keeps on giving.

Ever since loading Collection #1 in 2019, I have been extra cautious about dealing with credential stuffing lists. The 400+ comments on that blog post will give you just a little taste of how much attention that exercise garnered. Frankly, it was a significant contributor to the feeling that it was all getting a bit too much, leading to the decision that HIBP needed to find another home (which fortunately, never eventuated). The primary issue with credential stuffing lists is that we can't attribute a given row to a specific source website or data breach, and we don't offer a service to look up credential pairs. As you'll see from many of the comments on that post, I had angry people upset that, without knowing specifically which password was exposed in the list, the knowledge that they were in there was not actionable. I disagree, because by loading those passwords into Pwned Passwords, there are now three easy ways to check if you're using a vulnerable one:

- Use the Pwned Passwords search page. Passwords are protected with an anonymity model, so we never see them (it's processed in the browser itself), but if you're wary, just check old ones you may suspect.

- Use the k-anonymity API. This is what drives the page in the previous point, and if you're handy with writing code, this is an easy approach and gives you complete confidence in the anonymity aspect.

- Use 1Password's Watchtower. The password manager has a built-in checker that uses the abovementioned API and can check all the passwords in your vault. (Disclosure: 1Password is a regular sponsor of this blog, and has product placement on HIBP.)

My vested interest in 1Password aside, Watchtower is the easiest, fastest way to understand your potential exposure in this incident. And in case you're wondering why I have so many vulnerable and reused passwords, it's a combination of the test accounts I've saved over the years and the 4-digit PINs some services force you to use. Would you believe that every single 4-digit number ever has been pwned?! (If you're interested, the ABC has a fantastic infographic using a heatmap based on HIBP data that shows some very predictable patterns for 4-digit PINs.)

As of the time of publishing this blog post, only the stealer logs have been loaded, and as mentioned earlier, the data in HIBP has been called "Synthient Stealer Log Threat Data". We intend to load the credential stuffing data as a separate corpus next week and call it "Synthient Credential Stuffing Threat Data", assuming it's sufficiently new and the accuracy is confirmed with our subscribers! We're doing this in two parts simply because of the scale of the data and the fact that we want to break it into two discrete corpuses given the data originates via different means. I'll revise this blog post accordingly after we finish our analysis.

Future

Something that is becoming more evident as we load more stealer logs is that treating them as a discrete "breach" is not an accurate representation of how these things work. The truth is that, unlike a single data breach such as Ashley Madison, Dropbox, or the many other hundreds already in HIBP, stealer logs are more of a firehose of data that's just constantly spewing personal info all over the place. That, combined with the duplication of previously seen data, means that we need a rethink on this model. The data itself is still on point, but I'd like to see HIBP better reflect that firehose analogy and provide a constant stream of new data. Until then, Synthient's Threat Data will still sit in HIBP and be searchable in all the usual ways.