Many people will land on this page after learning that their email address has appeared in a data breach I've called "Collection #1". Most of them won't have a tech background or be familiar with the concept of credential stuffing so I'm going to write this post for the masses and link out to more detailed material for those who want to go deeper.

Let's start with the raw numbers because that's the headline, then I'll drill down into where it's from and what it's composed of. Collection #1 is a set of email addresses and passwords totalling 2,692,818,238 rows. It's made up of many different individual data breaches from literally thousands of different sources. (And yes, fellow techies, that's a sizeable amount more than a 32-bit integer can hold.)

In total, there are 1,160,253,228 unique combinations of email addresses and passwords. This is when treating the password as case sensitive but the email address as not case sensitive. This also includes some junk because hackers being hackers, they don't always neatly format their data dumps into an easily consumable fashion. (I found a combination of different delimiter types including colons, semicolons, spaces and indeed a combination of different file types such as delimited text files, files containing SQL statements and other compressed archives.)

The unique email addresses totalled 772,904,991. This is the headline you're seeing as this is the volume of data that has now been loaded into Have I Been Pwned (HIBP). It's after as much clean-up as I could reasonably do and per the previous paragraph, the source data was presented in a variety of different formats and levels of "cleanliness". This number makes it the single largest breach ever to be loaded into HIBP.

There are 21,222,975 unique passwords. As with the email addresses, this was after implementing a bunch of rules to do as much clean-up as I could including stripping out passwords that were still in hashed form, ignoring strings that contained control characters and those that were obviously fragments of SQL statements. Regardless of best efforts, the end result is not perfect nor does it need to be. It'll be 99.x% perfect though and that x% has very little bearing on the practical use of this data. And yes, they're all now in Pwned Passwords, more on that soon.

That's the numbers, let's move onto where the data has actually come from.

Data Origins

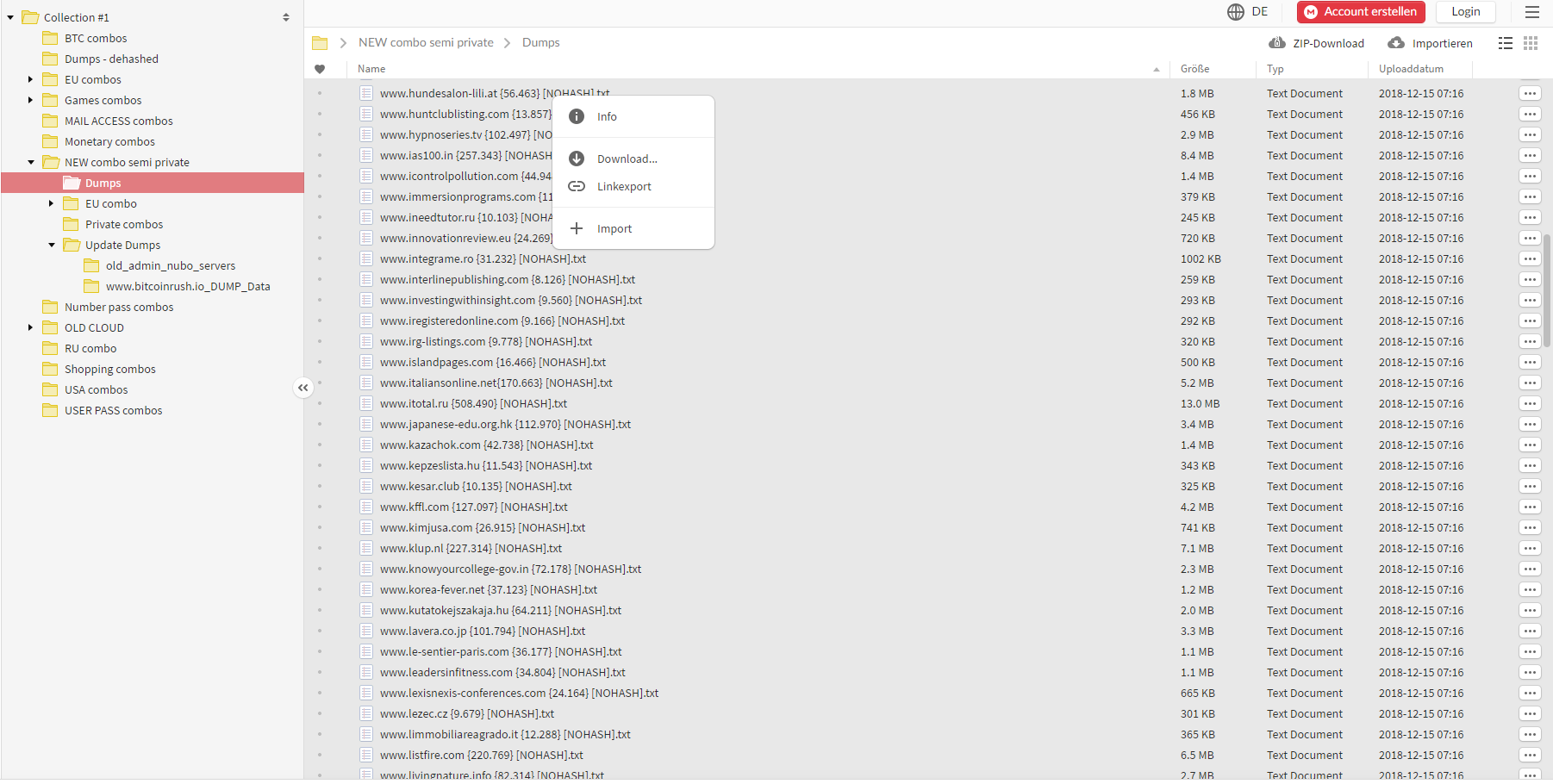

Last week, multiple people reached out and directed me to a large collection of files on the popular cloud service, MEGA (the data has since been removed from the service). The collection totalled over 12,000 separate files and more than 87GB of data. One of my contacts pointed me to a popular hacking forum where the data was being socialised, complete with the following image:

As you can see at the top left of the image, the root folder is called "Collection #1" hence the name I've given this breach. The expanded folders and file listing give you a bit of a sense of the nature of the data (I'll come back to the word "combo" later), and as you can see, it's (allegedly) from many different sources. The post on the forum referenced "a collection of 2000+ dehashed databases and Combos stored by topic" and provided a directory listing of 2,890 of the files which I've reproduced here. This gives you a sense of the origins of the data but again, I need to stress "allegedly". I've written before about what's involved in verifying data breaches and it's often a non-trivial exercise. Whilst there are many legitimate breaches that I recognise in that list, that's the extent of my verification efforts and it's entirely possible that some of them refer to services that haven't actually been involved in a data breach at all.

However, what I can say is that my own personal data is in there and it's accurate; right email address and a password I used many years ago. Like many of you reading this, I've been in multiple data breaches before which have resulted in my email addresses and yes, my passwords, circulating in public. Fortunately, only passwords that are no longer in use, but I still feel the same sense of dismay that many people reading this will when I see them pop up again. They're also ones that were stored as cryptographic hashes in the source data breaches (at least the ones that I've personally seen and verified), but per the quoted sentence above, the data contains "dehashed" passwords which have been cracked and converted back to plain text. (There's an entirely different technical discussion about what makes a good hashing algorithm and why the likes of salted SHA1 is as good as useless.) In short, if you're in this breach, one or more passwords you've previously used are floating around for others to see.

So that's where the data has come from, let me talk about how to assess your own personal exposure.

Checking Email Addresses and Passwords in HIBP

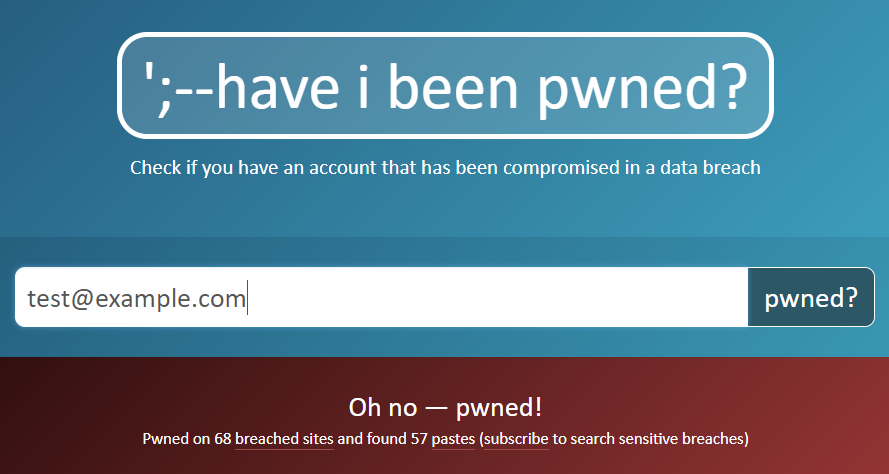

There'll be a significant number of people that'll land here after receiving a notification from HIBP; about 2.2M people presently use the free notification service and 768k of them are in this breach. Many others, over the years to come, will check their address on the site and land on this blog post when clicking in the breach description for more information. These people all know they were in Collection #1 and if they've read this far, hopefully they have a sense of what it is and why they're in there. If you've come here via another channel, checking your email address on HIBP is as simple as going to the site, entering it in then looking at the results (scrolling further down lists the specific data breaches the address was found in):

But what many people will want to know is what password was exposed. HIBP never stores passwords next to email addresses and there are many very good reasons for this. That link explains it in more detail but in short, it poses too big a risk for individuals, too big a risk for me personally and frankly, can't be done without taking the sorts of shortcuts that nobody should be taking with passwords in the first place! But there is another way and that's by using Pwned Passwords.

This is a password search feature I built into HIBP about 18 months ago. The original intention of it was to provide a data set to people building systems so that they could refer to a list of known breached passwords in order to stop people from using them again (or at least advise them of the risk). This provided a means of implementing guidance from government and industry bodies alike, but it also provided individuals with a repository they could check their own passwords against. If you're inclined to lose your mind over that last statement, read about the k-anonymity implementation then continue below.

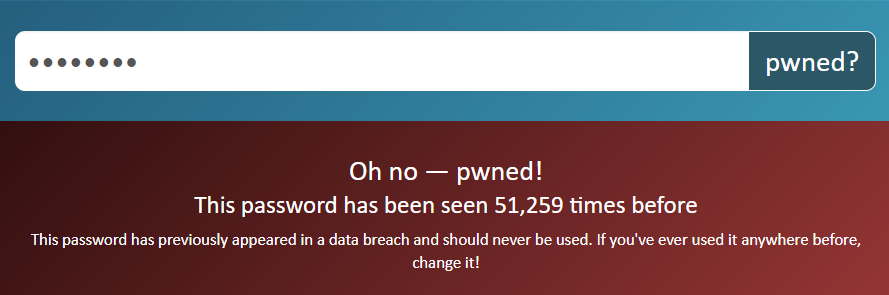

Here's how it works: let's do a search for the word "P@ssw0rd" which incidentally, meets most password strength criteria (upper case, lower case, number and 8 characters long):

Obviously, any password that's been seen over 51k times is terrible and you'd be ill-advised to use it anywhere. When I searched for that password, the data was anonymised first and HIBP never received the actual value of it. Yes, I'm still conscious of the messaging when suggesting to people that they enter their password on another site but in the broader scheme of things, if someone is actually using the same one all over the place (as the vast majority of people still do), then the wakeup call this provides is worth it.

As of now, all 21,222,975 passwords from Collection #1 have been added to Pwned Passwords bringing the total number of unique values in the list to 551,509,767.

Whilst I can't tell you precisely what password was against your own record in the breach, I can tell you if any password you're interested in has appeared in previous breaches Pwned Passwords has indexed. If one of yours shows up there, you really want to stop using it on any service you care about. If you have a bunch of passwords and manually checking them all would be painful, give this a go:

If you use 1Password account you now have a brand new Watchtower integrated with @haveibeenpwned API. Thank you, @troyhunt ❤️

— Roustem Karimov (@roustem) May 3, 2018

Also, looks like I have to update some passwords ? pic.twitter.com/toyyNRPI4h

This is 1Password's Watchtower feature and it can take all your stored passwords and check them against Pwned Passwords in one go. The same anonymity model is used (neither 1Password nor HIBP ever see your actual password) and it enables bulk checking all in one go. I'm conscious that many people reading this won't be using a password manager of any kind in the first place and that's an absolutely pivotal part of how to deal with this incident so I'll come back to that a little later. Apparently, this feature along with integrated HIBP searches and notifications when new breaches pop up is one of the most-loved features of 1Password which is pretty cool! For some background on that, without me knowing in advance, they launched an early version of this only a day after I released V2 with the anonymity model (incidentally, that was a key motivator for later partnering with them):

Hey, you know what would be cool? If @1Password was to integrate with my newly released Pwned Passwords k-Anonymity model so you could securely check your exposure against the service (it'd have to be opt in, of course). Oh wow - look at this! https://t.co/RCspu1kNtR

— Troy Hunt (@troyhunt) February 22, 2018

For those using Pwned Passwords in their own systems (EVE Online, GitHub, Okta et al), the API is now returning the new data set and all cache has now been flushed (you should see a very recent "last-modified" response header). All the downloadable files have also been revised up to version 4 and are available on the Pwned Passwords page via download courtesy of Cloudflare or via torrents. They're in both SHA1 and NTLM formats with each ordered both alphabetically by hash and by prevalence (most common passwords first).

Why Load This Into HIBP?

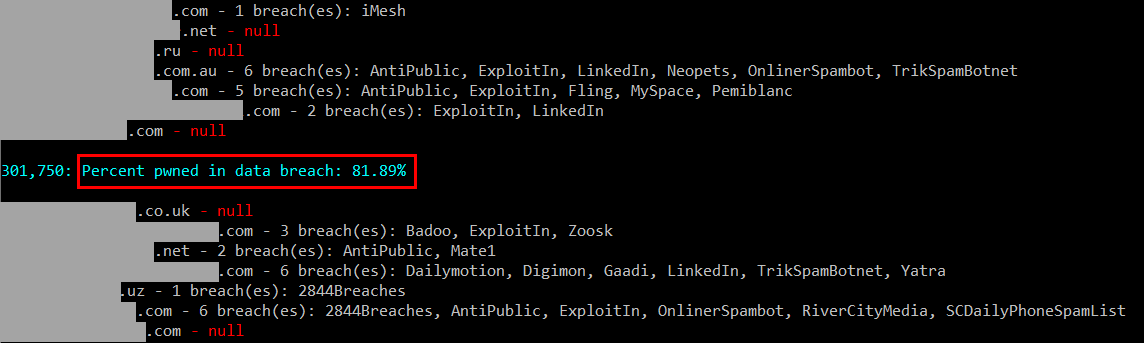

Every single time I came across a data set that's not clearly a breach of a single, easily identifiable service, I ask the question - should this go into HIBP? There are a number of factors that influence that decision and one of them is uniqueness; is this a sufficiently new set of data with a large volume of records I haven't seen before? In determining that, I take a slice of the email addresses and ran them against HIBP to see how many of them had been seen before. Here's what it looked like after a few hundred thousand checks:

In other words, there's somewhere in the order of 140M email addresses in this breach that HIBP has never seen before.

The data was also in broad circulation based on the number of people that contacted me privately about it and the fact that it was published to a well-known public forum. In terms of the risk this presents, more people with the data obviously increases the likelihood that it'll be used for malicious purposes.

Then there's the passwords themselves and of the 21M+ unique ones, about half of them weren't already in Pwned Passwords. Keeping in mind how this service is predominantly used, that's a significant number that I want to make sure are available to the organisations that rely on this data to help steer their customers away from using higher-risk passwords.

And finally, every time I've asked the question "should I load data I can't emphatically identify the source of?", the response has always been overwhelmingly "yes":

If I have a MASSIVE spam list full of personal data being sold to spammers, should I load it into @haveibeenpwned?

— Troy Hunt (@troyhunt) November 15, 2016

People will receive notifications or browse to the site and find themselves there and it will be one more little reminder about how our personal data is misused. If - like me - you're in that list, people who are intent on breaking into your online accounts are circulating it between themselves and looking to take advantage of any shortcuts you may be taking with your online security. My hope is that for many, this will be the prompt they need to make an important change to their online security posture. And if you find yourself in this data and don't feel there's any value in knowing about it, ignore it. For everyone else, let's move on and establish the risk this presents then talk about fixes.

What's the Risk If My Data Is in There?

I referred to the word "combos" earlier on and simply put, this is just a combination of usernames (usually email addresses) and passwords. In this case, it's almost 2.7 billion of them compiled into lists which can be used for credential stuffing:

Credential stuffing is the automated injection of breached username/password pairs in order to fraudulently gain access to user accounts.

In other words, people take lists like these that contain our email addresses and passwords then they attempt to see where else they work. The success of this approach is predicated on the fact that people reuse the same credentials on multiple services. Perhaps your personal data is on this list because you signed up to a forum many years ago you've long since forgotten about, but because its subsequently been breached and you've been using that same password all over the place, you've got a serious problem.

By pure coincidence, just last week I wrote about credential stuffing attacks and how they led many people to believe that Spotify had suffered a data breach. In that post, I embedded a short video that shows how easily these attacks are automated and I want to include it again here:

Within the first 15 seconds, the author of the video has chosen a combo list just like the one three quarters of a billion people are in via this Combination #1 breach. Another 30 seconds and the software is testing those accounts against Spotify and reporting back with email addresses and passwords that can logon to accounts there. That's how easy it is and also how indiscriminate it is; it's not personal, you're just on the list! (For people wanting to go deeper, check out Shape Security's video on credential stuffing.)

To be clear too, this is not just a Spotify problem. Automated tools exist to leverage these combo lists against all sorts of other online services including ones you shop at, socialise at and bank at. If you found your password in Pwned Passwords and you're using that same one anywhere else, you want to change each and every one of those locations to something completely unique, which brings us to password managers.

Get a Password Manager

You have too many passwords to remember, you know they're not meant to be predictable and you also know they're not meant to be reused across different services. If you're in this breach and not already using a dedicated password manager, the best thing you can do right now is go out and get one. I did that many years ago now and wrote about how the only secure password is the one you can't remember. A password manager provides you with a secure vault for all your secrets to be stored in (not just passwords, I store things like credit card and banking info in mine too), and its sole purpose is to focus on keeping them safe and secure.

A password manager is also a rare exception to the rule that adding security means making your life harder. For example, logging on to a mobile app is dead easy:

Password managers are one of the few security constructs that actually make your life easier. Take logging onto a mobile app with @1Password on iOS: tap the email field, choose the account, Face ID, login button, job done! Not a single character typed ? pic.twitter.com/6ZKcGHfHhq

— Troy Hunt (@troyhunt) January 13, 2019

I chose the password manager 1Password all those years ago and have stuck with it ever it since. As I mentioned earlier, they partnered with HIBP to help drive people interested in personal security towards better personal security practices and obviously there's some neat integration with the data in HIBP too (there's also a dedicated page explaining why I chose them).

If a digital password manager is too big a leap to take, go old school and get an analogue one (AKA, a notebook). Seriously, the lesson I'm trying to drive home here is that the real risk posed by incidents like this is password reuse and you need to avoid that to the fullest extent possible. It might be contrary to traditional thinking, but writing unique passwords down in a book and keeping them inside your physically locked house is a damn sight better than reusing the same one all over the web. Just think about it - you go from your "threat actors" (people wanting to get their hands on your accounts) being anyone with an internet connection and the ability to download a broadly circulating list Collection #1, to people who can break into your house - and they want your TV, not your notebook!

FAQs

Because an incident of this size will inevitably result in a heap of questions, I'm going to list the ones I suspect I'll get here then add to it as others come up. It'll help me handle the volume of queries I expect to get and will hopefully make things a little clearer for everyone.

Q. Can you send me the password for my account?

I know I touched on it above but it's always the single biggest request I get so I'm repeating it here. No, I can't send you your password but I can give you a facility to search for it via Pwned Passwords.

Q. How long ago were these sites breached?

It varies. The first site on the list I shared was 000webhost who was breached in 2015, but there's also a file in there which suggests 2008. These are lots of different incidents from lots of different time frames.

Q. What can I do if I'm in the data?

If you're reusing the same password(s) across services, go and get a password manager and start using strong, unique ones across all accounts. Also turn on 2-factor authentication wherever it's available.

Q. I'm responsible for managing a website, how do I defend against credential stuffing attacks?

The fast, easy, free approach is using the Pwned Passwords list to block known vulnerable passwords (read about how other large orgs have used this service). There are services out there with more sophisticated commercial approaches, for example Shape Security's Blackfish (no affiliation with myself or HIBP).

Q. How can I check if people in my organisation are using passwords in this breach?

The entire Pwned Passwords corpus is also published as NTLM hashes. When I originally released these in August last year, I referenced code samples that will help you check this list against the passwords of accounts in an Active Directory environment.

Q. I'm using a unique password on each site already, how do I know which one to change?

You've got 2 options if you want to check your existing passwords against this list: The first is to use 1Password's Watch Tower feature described above. If you're using another password manager already, it's easy to migrate over (you can get a free 1Password trial). The second is to check all your existing passwords directly against the k-anonymity API. It'll require some coding, but's its straightforward and fully documented.

Q. Is there a list of which sites are included in this breach?

I've reproduced a list that was published to the hacking forum I mentioned and that contains 2,890 file names. This is not necessarily complete (nor can I easily verify it), but it may help some people understand the origin of their data a little better.

Q. Will you publish the data in collections #2 through #5?

Until this blog post went out, I wasn't even aware there were subsequent collections. I do have those now and I need to make a call on what to do with them after investigating them further.

Q. Where can I download the source data from?

Given the data contains a huge volume of personal information that can be used to access other people's accounts, I'm not going to direct people to it. I'd also ask that people don't do that in the comments section.